Kefir is something like liquid yogurt.

It’s thick, white, creamy and bubbly and tastes tart, slightly sour and yeasty, like a cross between yogurt and buttermilk.

It’s one of the world’s oldest cultured milk products. Marco Polo himself sang its praises. And these days kefir’s being rediscovered by do-it-yourselfers and proponents of sustainable food systems. It’s one of the world’s oldest cultured milk products. Marco Polo himself sang its praises. And these days kefir’s being rediscovered by do-it-yourselfers and proponents of sustainable food systems.

Making converts to kefir

Warren Taylor of Snowville Creamery led a kefir workshop at last month’s annual conference of the Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association. He calls himself a “dairy evangelist.”

Before the workshop began, Taylor passed around buttons that read “Kefir: feel good.” The name derives from a Turkish word for well-being.

Taylor feels great, and hopes to convert others to what’s been his way of life for almost 40 years.

“I generally get up in the morning, my tummy’s pretty empty, I put about a quart of kefir in me. Goes deep, goes right through your stomach, and boom, right into your small intestines. Centuries ago this is how the herding people would consume their cultured products, big bowls of it. They would guzzle it.”

Centenarians of the Caucusus

Nomadic horsemen of the northern Caucasus mountains who drank the stuff reportedly lived past the century mark.

Some think the probiotic bacteria in kefir might be the reason why, but the only scientific proof of kefir’s medical benefits is a 2003 Ohio State University study that showed it curbed flatulence in those with lactose intolerance.

Reported rare side effects of drinking kefir include bloating, headache and acne.

Still, today it’s the most popular fermented milk in Russia, and in Uzbekistan, horse bladder saddle bags full of it still swing over front doors.

“You hang it in your doorway,” says Taylor, “and everyone who comes through the doorway slaps it, coming and going, to shake it and agitate it, and that makes it grow faster.”

It’s alive

It grows because it’s a living organism that you have to take care of every day.

"Real kefir is something that you keep like a pet.”

But Taylor says like many of the best things in life, real kefir can’t be bought.

“God can’t put kefir in a bottle," says Taylor. "The stuff that’s in the store that’s called kefir is not kefir.”

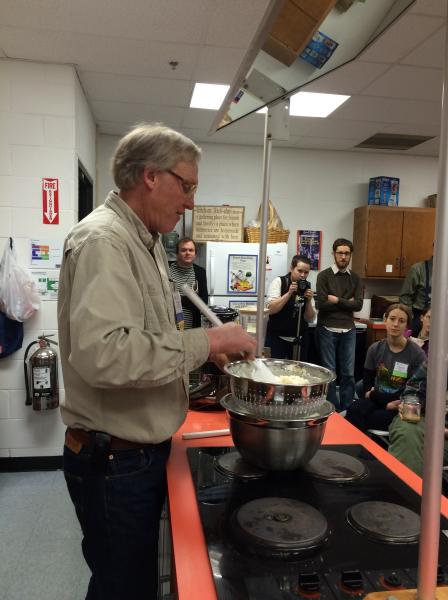

Demonstrating how he says anyone can make it at home, Taylor strains foamy liquid through a colander to isolate kefir “grains.” He’ll share some with workshop participants.

“Pass that around. You can get a smell, get an idea. We’re going to put those in little bottles for you.”

The grains are a gelatinous mass of bacteria and yeast, a symbiotic community of microorganisms. The small, irregular, opaque clumps look like cottage cheese or cauliflower. The grains are a gelatinous mass of bacteria and yeast, a symbiotic community of microorganisms. The small, irregular, opaque clumps look like cottage cheese or cauliflower.

Once plopped into a quantity of milk, kefir grains ferment the liquid. Then they’re strained out and added to fresh milk for use in successive batches.

A renewable source of nutrition

Kefir is a self-perpetuating food source of somewhat mysterious origin.

It’s believed that all the kefir grains in the world today are babies of a mother culture that came out of the Caucasus mountains thousands of years ago.

Warren Taylor calls it an enigma.

“It only exists because of human beings, but nobody can make it. The most sophisticated dairy lab in the world can’t make you a real kefir culture. You have to get it from somebody.”

A question at the workshop: “Is there a ratio of grains to milk?”

“Good question,” Taylor replied. “It depends on the temperature that it’s going to be growing at, because the warmer it is, the less kefir you need to milk, to have it grow out in the same period of time. How vigorous are the grains, how good is the milk? All of these things. So you just kind of get to know your kefir.” grow out in the same period of time. How vigorous are the grains, how good is the milk? All of these things. So you just kind of get to know your kefir.”

Sharing the grains and the method

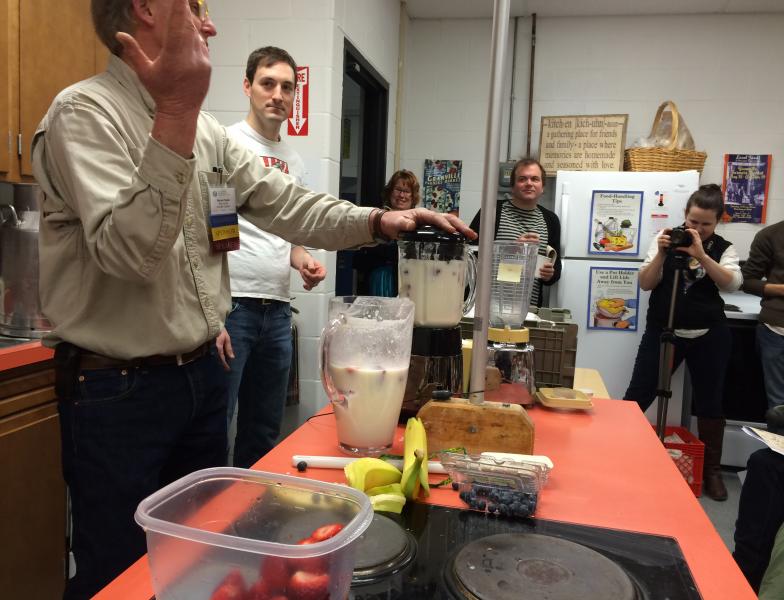

You can drink it plain, but Taylor brought a blender and made the workshop participants a kefir smoothie.

“We’re going to put fresh strawberries, and blueberries. I like bananas.”

Warren Taylor learned about kefir at college in a dairy technology class, but it took two years of searching before he could get grains shipped to him from Holland.

“That was the beginning of my kefir culture, and this is the same culture I’m going to share with you all today. So I’ve been drinking this since 1978.”

How many people has he shared his culture with?

“In the last nearly 40 years, thousands. I think it’s a very fundamental human idea, to share.”

“You’re going to give us some today?” “You’re going to give us some today?”

“Yes.”

“What am I going to do when I go home?”

“Put it in milk.”

“Well, how much?”

“Three parts milk to one part grains.”

“How long do you let it sit?”

“Until it coagulates, until it makes a gel, until it has acidity.”

“Like two hours?”

“Well, 24.”

Much longer than the 4 to 6 hours it takes to ferment yogurt.

“Kefir, buttermilk, sour cream," says Taylor, "take more like 24 hours, room temperature.”

Slightly alcoholic when ripe

Letting it sit even longer on your kitchen counter is called ripening, and that’s what Rachel Baillieul often does. what Rachel Baillieul often does.

“If you allow kefir to go on long enough you might get a little bit of an alcoholic taste," she says, "or an effervescence.”

Baillieul is an urban homesteader farming on two acres of soil in Columbus.

“I’m a home cook who is unafraid to try anything. That’s what started me down this road of fermentation. “

She’s teaching a workshop on the culinary aspects of kefir.

“So this is kefir that’s actually gone a little bit far. I forgot to put it in the fridge when I came yesterday. So it needed one less day.”

The grains are edible, too

A question comes up about how to handle the grains.

“Do you typically always filter them out prior to consuming the kefir?”

“No. They are consumable. And you have to decide, am I going to eat them? Am I going to press them together to make a sort of cheese? Am I going to feed them to my animals? Am I going to pass them to friends?”

She says they can be stored in a little bit of milk or water in the refrigerator. "I just recently pulled some out that I had just in water for about three months. They were still alive.”

Baillieuil belongs to a growing kefir community. Baillieuil belongs to a growing kefir community.

“I’m one of those crazy people who has cultures. So if you need things let me know.”

Snowville Creamery’s Warren Taylor believes the local foods movement along with a new reverence for lost arts creates the perfect climate for the growth of a shared kefir culture.

“We’re rediscovering community in this country.” |