The exhibition titled “Trenton Doyle Hancock: Skin and Bones, 20 Years of Drawing” fills several rooms at the Akron Art Museum. Three hundred drawings and paintings are displayed as well as what looks at first like graffiti.

The phrase “you deserve less” repeated hundreds of times in bold black letters splashes over two gallery walls. Letters, numbers and words are also embedded in many of Hancock’s sketches and drawings.

Story-telling is part of the art

“I’m not a writer,” he says, “but I write out of necessity to keep all of this going. I write before I make work; I write in the work; I write afterwards reflecting on the work. It's part of the process.”

The exhibition was launched in Hancock’s hometown at the Contemporary Arts Museum of Houston. There, as in Akron, he participated in the installation.

Akron’s Collection Manager Arnie Tunstall worked side-by-side with the artist.

“It has taken a long time," says Tunstall, “but it’s gone faster because of the artist here with us helping us do the installation and embellishing it with his words and his painting on the walls in addition to his artwork.”

“I don’t know how I expedited this process," says Hancock, “but it comes with the exhibition so I travel with it and put my personal touch to it.”

Childhood fantasies come to life

The work is intensely personal and full of fantasies Hancock’s lived with and illustrated since childhood.

“This is work I did when I was in the fifth grade. You see Torpedo Boy. He is a character that I originated  myself. And he is myself. And I made him because as a little kid I wanted to feel more super. So I started writing these stories and illustrating them. And Torpedo Boy was sort of my version of Superman.” myself. And he is myself. And I made him because as a little kid I wanted to feel more super. So I started writing these stories and illustrating them. And Torpedo Boy was sort of my version of Superman.”

Hancock’s career zoomed faster than a speeding bullet when he was invited to the Whitney Biennale Exhibition in New York more than a decade ago while he was still a grad student.

All about vision

But as a child, though gifted, he had problems.

“I got glasses. And that doesn’t make you feel like big man on campus really. But I started thinking about Clark Kent and how cool he is. He takes off his glasses and he becomes the archetypal superhero. So I thought I will follow suit, and I will put on a super suit.”

We notice that he now wears glasses with huge yellow frames.

“It’s become part of my identity. I said at some point I might as well go with it. And if I’m going to be blind I’m going to go blind in style.”

His vision is seriously impaired. “If I take these off then … it’s the great equalizer because everyone just looks like a fuzzy something I don’t know. I feel like artists become artists because they are trying to get over some kind of impairment. It’s all about vision at some level.”

Dreams and reality converge

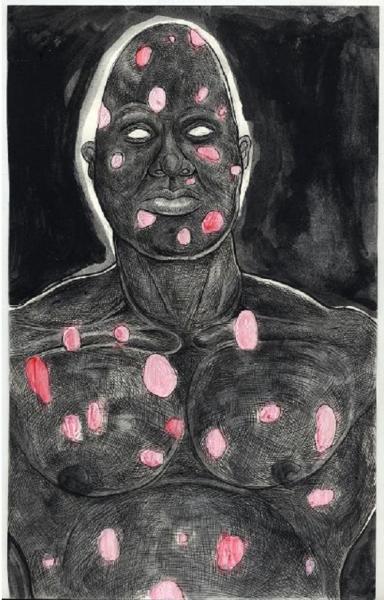

Haunting visions of scary creatures inhabit Hancock’s drawings and paintings as well as his dreams.

"Reality cycles back into this kind of subconscious murky water and then doubles back. And sometimes I can’t figure out what’s reality and what’s dreams, and what’s the past, what’s the present and future. It all gets conflated. And to me that’s why I keep doing it. Because I like that confusion. It’s very strange. “ out what’s reality and what’s dreams, and what’s the past, what’s the present and future. It all gets conflated. And to me that’s why I keep doing it. Because I like that confusion. It’s very strange. “

Strange and disturbing self-portraits are in the exhibition, as well as richly detailed but gruesome renderings. “How I know I must be getting at something,” he says, “is if it can scare me.”

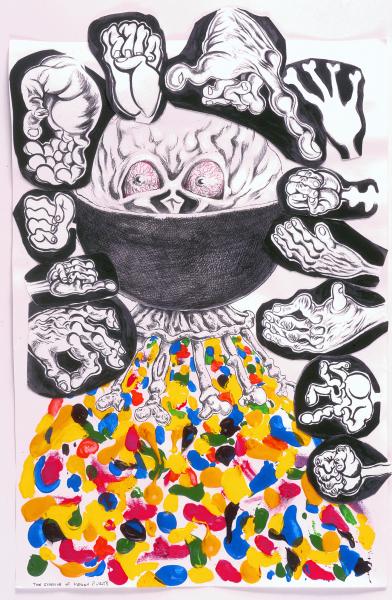

Epic mythological warfare

Weirdest of all is the cosmic battle between two imaginary tribes, the Mounds, who are part animal and part plant, and their mortal enemies, the Vegans. He calls it a story of good versus evil as well as fall and redemption.

Hancock says his Baptist preacher step-father taught him to appreciate the stories as well as the language of the Bible. Other influences include comic books, graphic novels, the history of art, and other so-called “outsider artists” from Hieronymous Bosch to Philip Guston.

“Outsider artist isn’t the term a lot of people use now," says Hancock. “It’s ‘visionary artist,’ people generally that aren’t trained in school but still have a passion to make things. Inspired, usually by divinity somehow. And I feel a kinship to it.”

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s “Skin and Bones” remains on view at the Akron Art Museum through Jan. 4th. |