Fear of sneezing

Growing up, Audra Beers had a fear of sneezing. Every sneeze and cough brought blinding pain. Beers thought what was happening to her was normal. It wasn’t until she was 37 that an unrelated sports injury led to an MRI, and the discovery of what was causing her lifetime of headaches, numbness, and painful sneezes. Every symptom, from the headaches to the neck pain suddenly made sense. She says “every single symptom I had was Chiari related." After decades undiagnosed, she finally knew what was causing her wide ranging maladies, and although it meant brain surgery, Beers was elated to finally know what was wrong with her.

She remains frustrated that the many doctors she saw over the years had never put the symptoms together under the name Chiari. She realized she wasn't "crazy" and,"that it truly was the Chiari that was causing all my issues.” Two surgeries later she has partial paralysis in her left side and continuing pain, but also peace of mind.

Building a better diagnosis

It’s estimated that 1 in 1000 people in the US have Chiari malformation. It’s named after Hans Chiari, a 19th century Austrian doctor who first described the disease. Chiari is caused by a slight malformation at the base of the skull that allows the hind-brain to slip down into the spinal column. This herniation, as it’s called, blocks the flow of spinal fluid, and causes terrible headaches that start in the back of the head. About 300,000 Americans are estimated to have Chiari, and many don’t even know they have it.

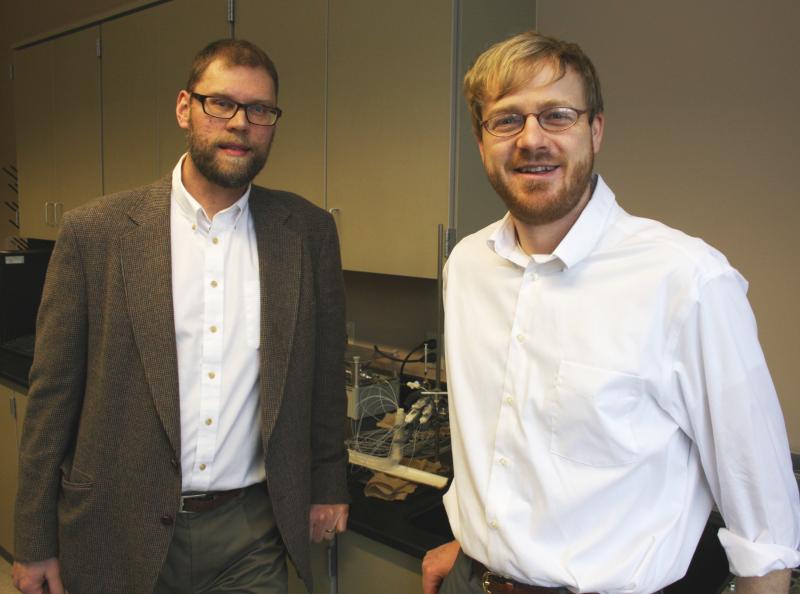

That got Rick Labuda working to improve the diagnosis of this mysterious condition. Labuda is head of the Conquer Chiari Foundation based in Pittsburgh. He has Chiari, AND he’s an electrical engineer. The combination gave him an idea. He says the conditions of Chiari, a skull that’s not large enough, and a brain that herniates and blocks the flow of fluid from the brain to the spine, "screams out for an engineering analysis and an engineering approach.” And that’s why Labuda and his foundation invested close to half a million dollars this year to set-up the Conquer Chiari Research Center at the University of Akron, run by mechanical engineers Frank Loth and Bryn Martin. Labuda is head of the Conquer Chiari Foundation based in Pittsburgh. He has Chiari, AND he’s an electrical engineer. The combination gave him an idea. He says the conditions of Chiari, a skull that’s not large enough, and a brain that herniates and blocks the flow of fluid from the brain to the spine, "screams out for an engineering analysis and an engineering approach.” And that’s why Labuda and his foundation invested close to half a million dollars this year to set-up the Conquer Chiari Research Center at the University of Akron, run by mechanical engineers Frank Loth and Bryn Martin.

Engineering a fluid flow model for Chiari

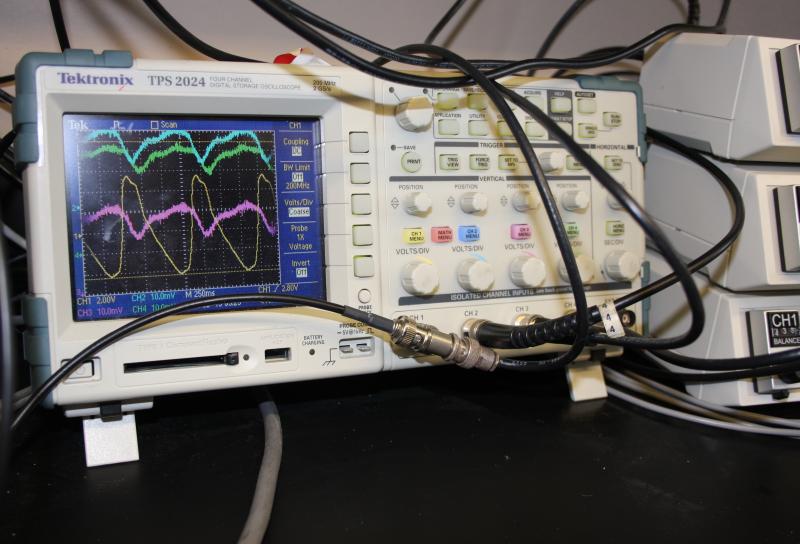

In the new lab, director Bryn Martin demonstrates his model of the human spine, complete with flowing cerebrospinal fluid, my finger acting as the Chiari blockage.  He's developing tools to measure the 1cc flow of cerebrospinal fluid that pulses in and out of the skull with every heartbeat, but the simulated blockage creates a jagged readout on the colored graph that measures the rhythm. He's developing tools to measure the 1cc flow of cerebrospinal fluid that pulses in and out of the skull with every heartbeat, but the simulated blockage creates a jagged readout on the colored graph that measures the rhythm.

Engineering professor Frank Loth is also part of the team. He says as the plastic spine model is refined, data from MRI images from living patients begin to make more sense, and the two are combined to build an accurate understanding of fluid dynamics inside the spine. Loth says combining the information from the model and patient MRI's helps them, "arrive at the true result." Loth says,"we’re not going to cut somebody open and do pressure measurements inside somebody’s body, we’re not going to do that.”

Bridging the creativity gap

Surgeons, for now, rely on intuition and experience to treat Chiari patients. But the engineers at Akron’s new Chiari research center are helping that effort by building a mechanical model of the disease based on anatomy and fluid dynamics in a new approach Martin calls neurohydrodynamics. Engineers, says Loth, "bring to the table a critical thinking methodology that’s different than the neurosurgeons." He and Martin have launched a multi-disciplinary attack to conquer Chiari.  They’ve enlisted a psychologist to study cognitive effects of the disease, and a molecular biologist to tackle questions of the chemistry inside the spine. They’ve enlisted a psychologist to study cognitive effects of the disease, and a molecular biologist to tackle questions of the chemistry inside the spine.

Martin says, as pioneers in this field, the center's main engineering challenge is putting enough imagination into creative problem solving. He says having time to test each idea, “is the barrier, not the technical aspects." By combining creativity and engineering Martin's immediate goal is to develop better diagnostic tools for clinicians hoping to one day conquer Chiari. |