In the kitchen of the Grafton Correctional Institution, 22 prison inmates in jumpsuits, hair nets and beard guards have finished peeling their onions. They clutch long, sharp knives tethered tightly to chopping boards as Brandon Chrostowski demonstrates the technique.

“So use that blade, pow, pow, pow, like this. OK. Should be quick, should be easy. Don’t forget. What are the two reasons you’re going to get hired?” A hand goes up. “Speed,” one of the student inmates answers. this. OK. Should be quick, should be easy. Don’t forget. What are the two reasons you’re going to get hired?” A hand goes up. “Speed,” one of the student inmates answers.

“Make someone money or save someone money,” says Chrostowski. “So speed would save someone money.”

A second year of second chances

Chrostowski owns Edwin’s, an upscale Cleveland restaurant. In this second year of his prison cooking class, graduates of the first class are already working for him at Shaker Square.

That’s Rich Anderson’s dream.

“I’m hoping to go through the Edwin’s program out there when I leave here. I leave in January. I leave real soon. So we finish this program up in  December and I’m hoping to get a job with him and he’s going to help me get going, ... start a new life.” December and I’m hoping to get a job with him and he’s going to help me get going, ... start a new life.”

Chrostowski turned his own life around when he got the chance to attend the Culinary Institute of America after some time behind bars.

“Nothing like what these men have to endure. I didn’t do a long stretch. A little time in county jail. It’s a lot more difficult what they’re doing and what they have to battle out of.”

Prayers answered

Rich Anderson is a recovering alcoholic.

“This was my sixth DUI. Had a problem with drinking ever since I was 17, 18.”

He pulled a long stretch.

“It kind of hit me where it hurt. Five years is a long time. In January, I’ll be finished with the whole five years.” He’d never worked in anything but construction and kept losing jobs because of his drinking. He worried about what would happen when he got out.

“I’ve been praying for a while for some kind of a sign, what maybe was to come when I leave here. I need something. I didn’t know where I was going.”

That changed last summer when he got into the cooking class. There was space for 22, but 40 applied. Anderson was one of the first.

“I seen the list go up in the  day room and I decided to sign up. It was a change. Thought I might like it, and I ended up really liking it. I mean it changed my whole life around. Now I really want to do it.” day room and I decided to sign up. It was a change. Thought I might like it, and I ended up really liking it. I mean it changed my whole life around. Now I really want to do it.”

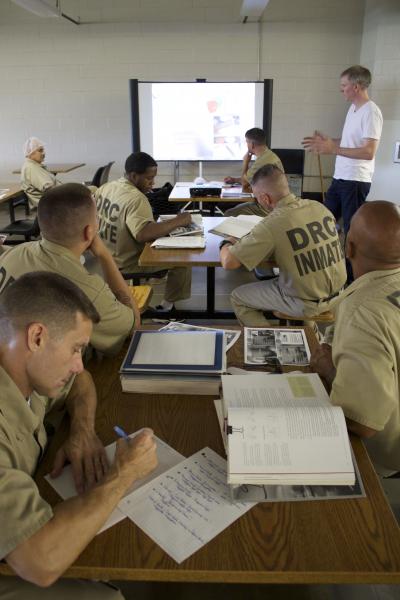

Chef Chrostowski wants them to do it right. So for the first four months of the six-month program, they stay in the classroom.

First the basics

“So knife 101. The kitchen's built on this, on the fundamentals," says Chrostowski. “These knife skills are going to help dictate the final product. So can

anyone tell me a couple reasons why the knife skill’s important?”

“Safety,” says a student.

“Safety, good,” says Chrostowski. “Anyone else?”

“So you can get the most use out of your product, too," another student answers.

“Right,” says Chrostowski. “The most use out of it. Alright.”

Students learn menu pricing, and profit and loss analysis as well as cooking and baking techniques. Their textbook, The Professional Chef, is the same one Chrostowski used at the Culinary Institute of America to master the art of French cuisine.

Jason Campbell of Canton hadn’t done much studying in a long time, but he doesn’t find it hard. Jason Campbell of Canton hadn’t done much studying in a long time, but he doesn’t find it hard.

“He makes it easy to understand, to be comfortable. I never thought school would be like this, so it’s like not actually like being in a classroom.”

Qualified and certified for culinary careers

When inmates graduate, they’ll be qualified to work with ServSafe certificates from the National Restaurant Association. If Chrostowski doesn’t hire them, his many friends in Cleveland’s tight-knit community of chefs usually will.

“In fact about a month ago a gentleman called me and within two days he was working full time, $11 an hour, and he’s making his way back. Another success story is my very own pastry chef, Tony Smith, who’s got a fabulous touch. He was actually in this class a year ago.”

Warden's Assistant Ron Armbruster knows from experience that Chrostowki’s students can cook. Warden's Assistant Ron Armbruster knows from experience that Chrostowki’s students can cook.

“The warden, myself, or the shift commander, we’ll sit and we’ll rate the meal as part of that graduation. So it’s kind of neat.”

A holistic approach

Armbruster says Grafton’s had cooking programs before through Ashland University, but he says Chrostowski’s holistic program is unique in the prison system in helping graduates find jobs.

"We went to dinner at Brandon’s restaurant a few months ago, and some of the gentlemen were working there that had been through the program already. Good to see them doing well on the outside.”

Lt. John Gannon handles security when the prisoners cook. He sees them change.

“From the first class with knife skills and cutting an onion or a potato. Just seeing how they look at things differently. Their attitudes change and the institution as well.”

Not just a number anymore

Not all the students are in it to get jobs. Ronald T. Martin of Painesville just wants to learn something he can use when he gets out of prison in April of 2017.

“Gives me different skills for when I get home. Some of us never cooked before. I have two daughters, ages 11 and 10. I like learning new meals for them instead of just mac and cheese.”

Chrostowski operates the prison cooking school without government support. He donates his own time and says the United Black Fund is the program’s biggest supporter. Chrostowski operates the prison cooking school without government support. He donates his own time and says the United Black Fund is the program’s biggest supporter.

Christopher Reynolds of Cleveland gets out next year. He says he’ll benefit from Chrostowski’s help, even if it doesn’t lead to a restaurant job.

“Brandon makes you feel like a person and not just a number, and it helps us feel somewhat normal in an environment like this.”

They’re getting a look at the outside, too, in this second year of the program. There’s video conferencing between Edwin’s Restaurant and the prison kitchen. |