The bad news in Summit County

Michael Johnson, chief of natural resources at Summit Metroparks, first brings us the bad news.

He asks us to imagine that in two years…"blue jays, cardinals, sparrows were going to be extinct. That’s exactly what’s happening with our bats.”

Johnson says caves at Liberty Park in Twinsburg were home to around 100,000 bats just two years ago. Johnson says caves at Liberty Park in Twinsburg were home to around 100,000 bats just two years ago.

Then, the deadly white nose syndrome swept through Summit County. He says recent sampling for one of the most common species came up dry.

He says in 2013, "we didn't catch any... They seemed to be almost entirely gone.”

The enormity of the impact is still sinking in. According to Johnson, "we’re looking at an extinction event.”

The spread of white nose syndrome

The four species of mouse-eared bats found in Ohio and the tiny tri-colored bat have been hardest hit by the white nose fungus. Up to 98 percent of the once common little brown bat are gone.

The fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) was first found in a cave in New York in 2006, most likely transported from Europe on a hiker’s boot. It’s now spread to 25 states and five Canadian provinces. An estimated 7 million bats have died from the disease.

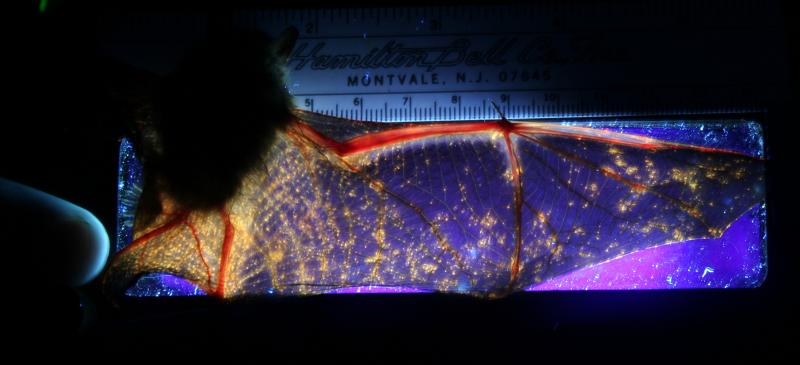

The cold-loving fungus attacks bats while they’re hibernating, siphoning their energy reserves. When they should be sleeping, they awaken weakened, and without food, they perish.

More bad news

Hazel Barton studies cave ecosystems at the University of Akron. She’s found that the fungus that causes white nose syndrome not only lives on bats, it thrives indefinitely on the cave floor. Her findings dash hopes that remnant populations could someday repopulate contaminated caves.

“If you wait a hundred years, you still have enough fungus in that environment that bats could potentially be infected.”

She says with their slow reproductive rate it could be 10,000 years before the hardest hit species rebound, assuming any survive at all. She says with their slow reproductive rate it could be 10,000 years before the hardest hit species rebound, assuming any survive at all.

But there is a glimmer of hope. The imported fungus is already changing, and is slightly less deadly now than when it first arrived six years ago.

Her findings suggest that the organism, "is already starting to adapt to our bat population and maybe reducing how quickly it kills.”

She thinks that adaptation actually makes the fungus more efficient at infecting bats.

Now for the good news

Grad student Kelsey Njus has spent countless hours growing various bat fungi in Barton’s lab.

She’s discovered what could make one species of North American bat, the rare Virginia big-eared bat, resistant to white nose syndrome.

Njus says, even though the big-eared bats carry the white nose fungus, "it’s not killing them, it’s not doing anything to them, they’re fine.”

Njus was determined to find out why.

She did molecular testing of tiny hair samples from the big-eared bat, looking for clues to its immunity.

She found a yeast that naturally grows on the bats’ fur, and the bats comb this dead yeast all over their bodies.

Njus believes the yeast could be inhibiting the growth of the fungus.

The yeast produces a slightly acidic, waxy yellow paste - a type of fatty acid that Njus thinks makes the bats' skin and fur, "inhospitable to a lot of pathogenic organisms," including the white nose fungus.

Njus tested the yeast’s ability to fight the fungus in the lab, and found that the yeast, “is completely inhibiting" the growth of the analogue to the white nose fungus in culture.

It’s the first ray of hope in what’s been six years of bat gloom.

She says it's, “the best news that I’ve discovered in a while.”

But Njus and Hazel Barton both caution that the discovery of resistance in one bat species is unlikely to help other bats escape the relentless scourge of white nose syndrome. |